The Vibrant Art Of Roxbury's Ekua Holmes Recalls The Harlem Renaissance

By Kevin C. Peterson

Originally published by WBUR

"Bus Stop" by Ekua Holmes.

Ekua Holmes is a welcome anachronism in African-American art, a woman who illuminates contemporary painting by embracing an aesthetic from the past.

Ostensibly self-conscious in the genre of representational art, the Roxbury native deftly salutes African-American luminaries who preceded her with stunning vibrancy — extending a clear-eyed perspective and a verve that serve to open new imaginative and intellectual vistas. She also weds herself to the idea that art should carry with it crisp social commentary, editorials on the state of black America.

Not since the Harlem Renaissance during the 1920s and '30s has there been a high-profile movement defining black culture as that movement so forcefully did. The brilliant works of William H. Johnson, Archibald Motley and Jacob Lawrence are examples of the epic quality of painting produced during that era.

Holmes, whose work is now on display at Simmons College, is a recognizable descendant of that school of painting, someone who stoically offers tales on canvas about the human condition — ranging from the joyful lemon juice of existence to the bracing blues that attend the cadence of our days. Her pictorial gestures showcase coherent, linear storytelling and urbane accessibility.

Deeply introspective and at every moment alert about the disposition of her subject, Holmes, who still lives in Roxbury, has a knack for raising the vernacular of the streets and common social situations into a private and noble language of lofty contemplation, a way of transitioning mundane scenes into allegorical insight.

To outsiders, the 62-year-old Holmes is mostly modest, often speaking in soft, dulcet tones that refract the visual choices she consistently makes in her paintings. As Holmes, who teaches at the Mass. College of Art, discusses her work, her gestures are graceful, nuanced and reminiscent of bodily movement learned from the long hours of ballet practice she endured as a youth in Roxbury at the Elma Lewis School for the Performing Arts. And like Lewis, that implacable doyenne who reigned for decades over the black arts community in Boston, Holmes reaches for any imaginative ideal, any plausible entry to the categories of the sublime, and any possible lesson that can be gleaned from the past.

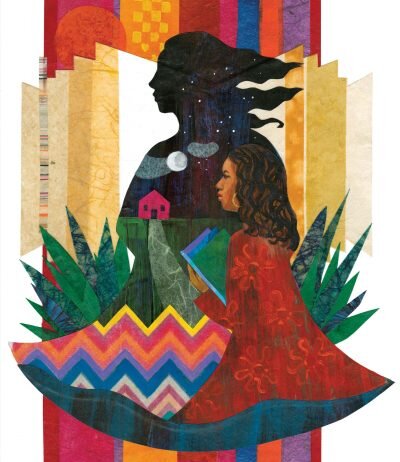

"Out of Wonder: House on Mango Street" by Ekua Holmes. (Courtesy of the artist)

“The Art of Ekua Holmes” will be on exhibit at Simmons College’s Center for the Study of Children’s Literature as part of its Summer Institute’s “(im)possible dreams” series. The display is open to the public through July 27, with the official opening on July 11.

The exhibit mostly displays Holmes’ paintings for the children's books she has recently illustrated, including her works on Fannie Lou Hamer, titled “Voice of Freedom” and “Out of Wonder, Poems Celebrating Poets.” The Hamer book, produced with writer Carole Boston Weatherford, garnered a children’s book trifecta: The Caldecott Honor Book, The Robert F. Sibert Honor Book and the John Steptoe New Talent Coretta Scott King Award.

The artwork in each book illustrates what writer Toni Morrison has called “rememory,” the African-American aggregation of past group experiences, and the capacity to recall individual and collective history by revisiting tragic and significant incidents.

"House on Mango Street" is a portrait of ebony beauty that highlights the mien of African-American womanhood. Characterized by its angular shapes and bombastic colors, it evokes reflection into the past, suggesting a primordial space that is home. A young black woman traverses time with books of knowledge in her hands, perhaps seeking a pathway to wisdom. The pull of the feminine mystique is palpable.

"Sufficient Grace" by Ekua Holmes. (Courtesy of the artist)

In "Bus Stop,” Holmes captures the urban landscape with power and pathos. A father sits wordless with his young boy on a bench, the full blaze of the city environs depicted gloriously in the background. The composition conveys agency, ambiguity and thick symbolic representationalism.

So too, "Sufficient Grace" is a study of sepia serenity and itself an essay on the complexity that drapes the interior life. An octogenarian church lady models a floral-patterned headpiece, the brim adorning her regal and gaudy Sunday religious wardrobe. The espresso-hued woman seems to hold the past and present in careful abeyance, her hauteur ennobling and suggestive of what writer Ralph Ellison has called the “rich abundance of warmth and human sympathy.”

Ellison’s quote is so telling of Holmes' work generally, which shows, at every turn, great humanity, a nod to past artistic masters and an ability to speak elegant truthfulness.